It was a great pleasure to welcome Colin Wiggins, Special Projects Curator at The National Gallery, to deliver the Christmas Lecture for the Bruton Art Society.

It was a great pleasure to welcome Colin Wiggins, Special Projects Curator at The National Gallery, to deliver the Christmas Lecture for the Bruton Art Society.

For several years Colin has managed The National Gallery’s scheme for offering associate fellowships to distinguished contemporary artists to work in the Gallery alongside the permanent collection. Notable holders of the fellowship have included Bridget Riley, Paula Rego, Maggie Hambling, Peter Blake and Frank Auerbach.

Often it might be thought that The National Gallery, which is dedicated to Old Master Paintings prior to 1900, would have little relevance for the contemporary art world. Colin showed that this was far from the case. He began by reminding us that The National Gallery was established originally, in 1824, with the explicit mission of providing contemporary British artists with first rate examples of the greatest art of the past to study and emulate.

This was in the days when Turner and Constable were leading practitioners in this country. Such artists seem to us to be old masters themselves these days, and we might think that the national collection has less to offer more recent figures, who appear to have moved so far away from traditional art practices. One of the reasons for setting up the scheme of associate artists was to counter this idea , and encourage a re-engagement with the past. This was not a question of persuading the modern artists to imitate the old master, but rather to enter into a dialogue with them. In fact most serious artists do this in any case. But the great advantage of this scheme is that it can make the process apparent and provide a context for it to develop further.

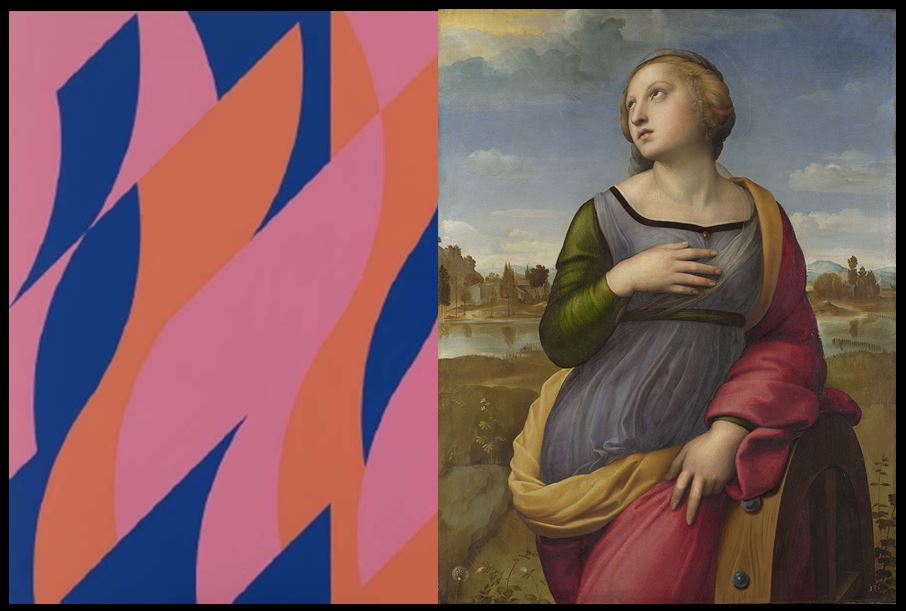

In discussing the responses of individual artists, Colin chose well, to demonstrate the variety and richness of the engagements. These ranged from the pure abstract paintings of Bridget Riley to the hyper-realistic sculptures of Ron Mueck. Bridget Riley sees all paintings as ‘abstracts’, and responded to the formal beauty of works in the collection. A notable example of this is when she responded to curves in Raphael’s St. Catherine and created her own abstract pattern from them [Fig. 1]. This is a reminder that all great art, whether abstract or representation, has to work as a design to be effective.

Ron Mueck, who was a trained realistic model maker before becoming a sculptor, responded more thematically. Noticing the great preponderances of Mothers and Child in the gallery (a reflection of the fact that European art for most of its history has been principally patronized by the Church), he developed his own versions of nativity, including an unforgettably explicit image of a mother with just born child (umbilical cord still attached) and a beautiful massive model of a heavily pregnant woman .

Other artists who used their fellowships to question the roles of traditional artists were Paula Rego and Peter Blake. Rego originally turned down the offer of a fellowship. She said she did not want to work with a collection that was so heavily biased towards the male. This is a fair point as only 6 pictures in the gallery’s collection of 2,300 are by women. Furthermore, the male view of women presented in the gallery could be criticized as stereotyped and sexist. In the end Rego decided to take up the challenge and produced a remarkable image of a sleeping man, echoing the story of St. Joseph.

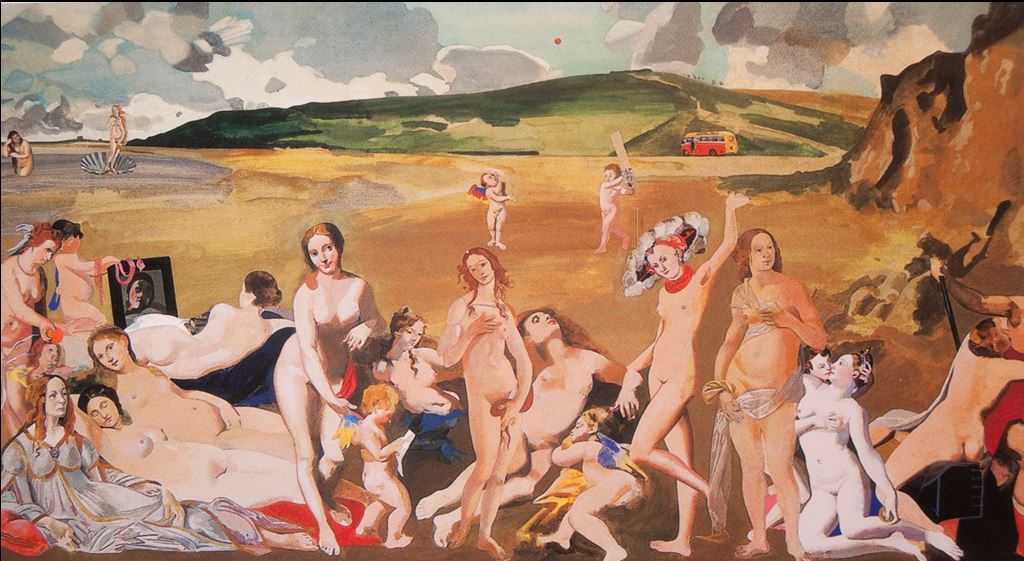

Peter Blake, on the other hand, might be said to have relished the male stereotypes, though in a characteristically playful manner. Seeing Constable’s image of Weymouth Bay before it had become a seaside resort, he decided to bring it up to date by having all the Venuses in the National Gallery cavorting along the shore [Fig. 3] . A particularly nice touch was the coach in the background, providing the transport for this works outing.

Colin also included the thoughtful and considered responses of Frank Auerbach, the grand old master of British painting who has recently had such an impressive retrospective at Tate Britain. Since his days as a student at the Royal College of Art, Auerbach has gone regularly to the National Gallery to make studies of the compositions of the old masters. Colin showed many of the sketches – often very rapid ones – that capture and explore the subtleties of grand compositions. These are deep thoughts about painting and design, showing the quality of vision that is worked out in his own complex paintings – as in his version of Rubens’ Sampson and Delilah.

The lecture was a true inspiration, and one that made one want to rush to the National Gallery to look anew at the treasure that they had there, and to think more about the things are our artists have discovered. At the time that the National Gallery was founded British art had an uncertain status. Nowadays it is riding high in the international art world. One wonders how much the engagement with the National Gallery that Colin’s lecture revealed might have had a hand in this transformation.

Will Vaughan